I won a grant from the American-Scandinavian Foundation to photograph Greenland’s melting glaciers at night

The talk at the Yale Club of New York covers what is was like seeing global warming in person and how it felt to sleep next to the strange ice sheet which stretches for 2,000 miles.

I tried not to think about the eight hour trek to the glacier where I was to photograph. Except for trips to Quebec and Newfoundland, I had never hiked more than one or two hours; I had never pitched a tent, used a campfire, or owned a backpack before either.

Eight Hour Trek

I started in the morning, figuring it might take four hours at most; it took double that (I laughed to myself when I first gauged the distance on the map while sitting in my apartment in New York, thinking it would only be about a two hour walk!). I was there to document environmental change as well as to capture the haunting primordial beauty of at night Greenland, funded by a grant from the American-Scandinavian Foundation.

After walking for about three hours, I came through a pristine valley with a rushing stream, beyond which was a high, nearly-vertical cliff. How could I get up there? Nevermind…I didn’t want to think too much about it. Oddly, there were a pack of Spanish travers coming down (there were many in Southern Greenland, due to two trekking centers there). One man descending lost his footing and almost crashed into me, which would cause both of us to fall about a hundred feet.

When they left single file down the path and back through the valley, I was alone again.

About halfway up, it became too steep to walk. A series of pull-ropes were precariously placed to aid the journey up; using them left me in a nearly horizontal position. This was harrowing, especially alone and with my 40 pound pack. But arriving at the top was stunning. The view overlooked a fjord and winding river reflecting the sun to the south; to the north was the start of the glacier leading to the ice sheet.

Descent Into Primordial World

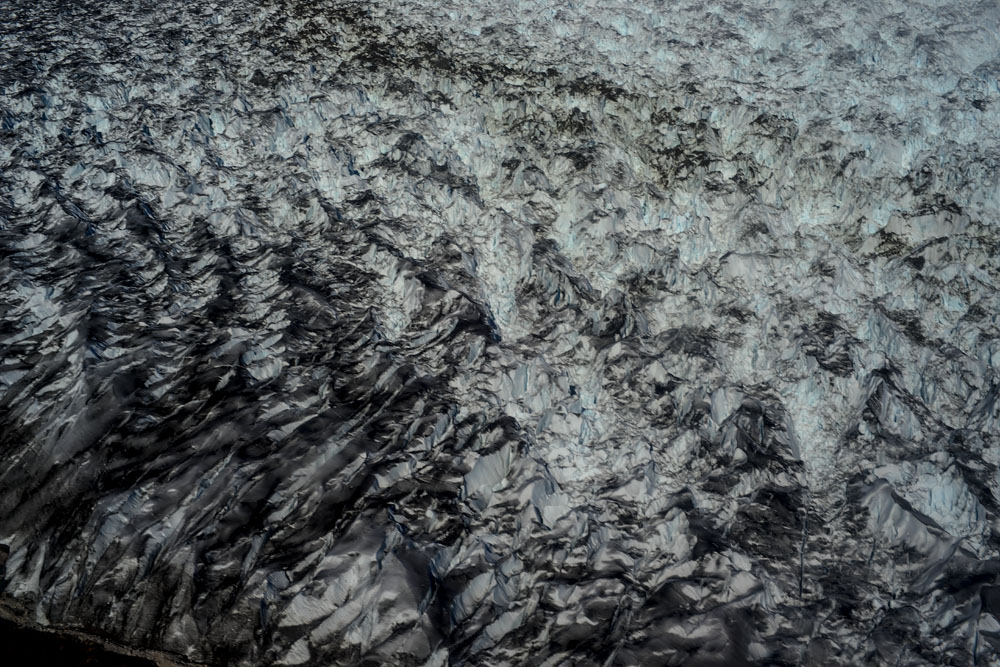

After walking through glacial pools and rocks, I descended on the other side to the glacier and ice sheet. The walk was like a trip back in time to a primordial world. It seemed like every hundred feet down looked like a thousand years back in time. Grass and low scrub bushes quickly gave way to just grass, then rocks with occasional plants and licken; then came only moss; to nearly no life form at the edge of the glacier except red or green algae spotted on rocks were the only indication of life.

At night, over the glacier and up towards the ice sheet were aurora borealis/Northern Lights. Having never seen them before, they stretched overhead dancing in terrifying beauty.

The sounds while sleeping along the glacier at night were strange and compelling. They ranged from frequent thundering ice breaks; baaing of unseen sheep perched across the fjord; the echo of invisible birds’ wings flapping overhead; and a low hum of a hidden river of water flowing underneath the ice (which seemed to echo my own blood pumping through my body).

Seeing Global Warming in Greenland

There was some direct evidence of global warming. Greenland is the second largest ice sheet (after Antarctica) and perhaps the most venerable, or certainly has the most impact to population centers of North America and Europe. I witnessed some changes myself.

In Narsarsuaq, the river that ran from the glacer to the fjord, about three miles long, is normally a stream but very occasionally it becomes a raging torrent when the melting waters burst from building up under the glacier. A flood happened while I was there. (I had planned camping there the week before–thankfully, I didn’t, or I could have died or been washed away.) I am told this is occuring more frequently and seems to be no longer rare.

Also, sheep farmers spoke of the lack of snow over the last handful of years. With less snow comes less water for the nascent tiny farming communities, hurting their overall output, forcing some farmers to leave or move away.

AirGreenland helicopter pilots are some of the most experienced flyers in the world–they have to be, given the extreme weather, danger, and lack of options if a craft goes down (if a flight is fifteen minutes late or there is no communication during that time, emergency recovery operations automatically take place.) One of the pilots who have taken people to the edge of the glacier for thirty years have noticed receding ice over the last few years. The glacier is “calving” or breaking into larger chunks more frequently too.

A “dead” glacier was receding more than usual, according to the local Danish guides. Outside Narsarsuaq, normally it would have been possible to trek completely to the ice at the spot where melting forms a river. But this has pulled back, making access on foot impossible.

It did seem warmer than usual too. I wore shorts most of the time during the day, and almost everyday was sunny. In 2017, dry conditions and higher than normal lead extremely rare forest fires. This is even more sad because trees grow only in a very limited area in the tip of southern Greenland where trees are barely four or five feet tall.

Also set in this extreme isolation is one the largest and fastest retreating glaciers. Moving at about three feet an hour–you can almost see it move–is the Helheim Glacier, aptly named after the world of the dead in Norse Mythology and is in East Greenland (a place even more isolated and so remote it has it’s own language, spoken by most of the six thousand inhabitants).

This is climate change incarnate; so intense is the rapid melting that there is even a special category of earthquake known as a glacialquake occurring there. This is where I plan to visit on my next trip and is the focus on another grant.

What Does Greenland and Stuytown Have in Common?

It is hard to comprehend a place like Greenland. To get some perspective about the remoteness of Greenland and lack of people, New York’s Stuyvesant Town at 40 acres vs all of Greenland’s 836,300 square miles–has about the same population: 60,000 people. Narsarsuaq, a town of 150 people is the site of one of two Greenlandic international airports; Qassiarsuk, across the fjord; and Igaliku, were the three towns I visited. As the crow flies, they were about ten miles or less apart from each other, but due to the lack of roads it could take half a day to get to each settlement via boat.

For example, Igaliku was a one hour boat ride through the icebergs and required a two hour hike to get to town. It was a lovely spot: sheep wandered around the Norse/Viking remnants from the 10th Century. Looking out across the fjord seemed similar space-wise to standing in Downtown New York and looking to New Jersey or Staten Island.

I landed in Narsarsuaq on August 15 and left about a little less than a month later on September 11. The temperature when I landed was about fifty-five degrees during the day, which seemed nearly perfect for hiking, but each day the temperature dropped about one degree; by the end of the trip it was a chilly 32 degrees.

After recovering in the only hotel in Narsarsuaq, which was originally a US army base (hence the airport with a long field big enough for jets to land on), I knew I had to tackle the biggest challenge first when I had the most energy and when the weather was warmest.

Towards the end of the trip, sleeping in the tent became too cold. In Qassiarsuk, an old Norse center, the only place to stay was a youth hostel which was full, so I crept into a Lutheran church, staying in a front room in my sleeping bag. I felt bad about sleeping in a church, but if there was any place that could offer help it should be a place of worship (besides, I was brought up a Lutheran, and felt there was some karmic connection is getting aid from a religious group that I was once a part of).

Technical Challenges

There were some technical challenges. First, and most basic, was how not to get lost. Fortunately, I used a mapping GPS app on my phone that did not require cell connection (most don’t, by the way). This proved invaluable. Since even during the day time many rock formations looks similar and because there were few paths, having a GPS guided app was important to not only find my way but allowed me to scout position locations where I could return at night.

Another technical challenge was power. I would be spending weeks away from an electrical outlet so powering my phone, camera, backup batteries, and SatPhone were crucial. For this I used a small portable solar panel. Folded into my backpack, whenever there was sun, I immediately pulled it out–fortunately, there were few rainy days.

I used a compact lightweight carbon fiber tripod to make long exposures. These ranged from a few minutes for the aurora borealis to longer and one hour. Due to the cold–another challenge–battery power drained more quickly, limiting the length of shots.

Started with Remote Landscapes

The whole idea behind the trip to Greenland started maybe fifteen years earlier. Initially, while at my first artist residency at Yaddo in upstate New York, I began photographing night landscapes. I then looked towards more rural places and found Quebec–near enough but another culture and remote. Looking on maps, I was fascinated with Newfoundland, supposedly the place where Norse Leif Erkisson departed Southern Greenland to North America. This lead me to look further East, to Greenland’s melting ice sheet where I completed the first part of this project.

Finding Greenland

Once I decided on Greenland, I researched specific places. Quite simply, I looked at satellite view of Google Maps. I searched around the coast, since that is the only part accessible, and looked for places where glaciers came close to the coast. I then tried to find towns that were near by, and prioritized which were close to glaciers and where within walking distance. Finally, I focused on settlements that are close to airports, particularly those hosting international flights. In Greenland, planes come only from Copenhagen or Reykjavik, Iceland. Narsarsuaq seemed perfect: it was within walking distance to glaciers; had international flights (from Iceland); and became a jumping off point to two other nearby communities in Southern Greenland.

Photographic Process at Night

My photographic process was to work mostly at night. Working at night is mysterious: I love how the landscape slowly reveals itself from the surrounding dark. Often I don’t really know what is being captured, so I just stand next to the camera, intuitively point it and take the picture. Later, I see what I photographed.

The artistic inspiration is loosely based on Hudson River Landscape painters such as Frederic Edwin Church, and others such as William Bradford, who explored the coast of Labrador. Additionally, the project is informed by Scandinavian and German cinema (Ingmar Bergman and Rainer Werner Fassbinder), and films my father would bring home to play in our darkened basement.

Also, books by Knud Rasmussen, The people of the Polar north; a record (1908); Rockwell Kent, N by E.; and Carstensen Riis and Christian Andreas, Two Summers in Greenland: An Artist’s Adventures Among Ice and Islands, in Fjords and Mountains where fascinating and inspirational.

Primordial Greenland

But one thing I was really interested in was centered on the parallels between dramatic climate changes and to capture a feeling of loss and mystery revealed through the contracting ice. Beyond documentation, the photographs crystallize a feeling of inertia taking place in the primordial landscape of Greenland.

As the raw land is exposed through the melting ice–as if a cultural truth is being unearthed–I feel there is a link between environment and culture. Just as Inuit life seems to be quietly abandoned in a churning retreat, so too is present day ice melting ignored. In both cases, there is a feeling of absence, impending human failure, tragedy, and the crushing force of nature being played out in a desolate place. I want to capture the immensity of the space in ethereal light, revealing both a lyrical beauty and inexorable horror in it’s destruction. I wanted to photograph this feeling of loss, discovery and change.

Comments are closed.